The Luckiest Man

One of the luckiest men I have ever had the honor of knowing is Dr. Edgar “Bud” Parsons. He survived World War II rifle company combat in the European Theatre, and served in the Air Force in Japan and Korea. He lived an fascinating and productive life by always being at the right place at an opportune time. For the Triangle area, Parsons brought his luck, expertise and fortitude with him to Chapel Hill, NC in 1960 to help transform the dream of a Research Triangle Institute and Research Triangle Park into a reality.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Edgar “Bud” Parsons passed away peacefully, surrounded by his loving family, on Memorial Day Sunday, May 26, 2013, at the age of 93. He was a humble, gentle soul who contributed greatly to our great state of North Carolina and our Chapel Hill community, and he will be dearly missed. His obituary can be found here: http://bit.ly/16960Ix

RTI International (formerly known as the Research Triangle Institute) is one of the world’s leading nonprofit development and research organizations, and is based in Research Triangle Park (RTP), North Carolina. It was developed deliberately within the RTP as an exemplary enterprise to facilitate the direction and success of RTP. RTI currently employs over 2,800 people worldwide and recorded assets exceeding $777 million last year. Research Triangle Park is currently home to over 170 companies located on 7,000 acres around the Raleigh/Durham International Airport, and employs well over 50,000 residents of North Carolina. RTP is now the largest research park in the United States and has led the way for the development of other technology parks across the state, notably Centennial Campus, Gateway University Research Park, the Charlotte Research Institute, and the Piedmont Triad Research Park.

Both RTI and RTP have certainly come a long way from their humble and rather shaky beginnings. In 1960, RTI only had one major client and very little funds left from their initial $500,000 fund-raising effort. Just four months after Edgar “Bud” Parsons arrived in Chapel Hill, N.C. with his wife and four small children, to be one of RTI’s first executives, they were already discussing lay-offs to conserve start-up capital. Parsons’ home on Eastwood Lake, where he still resides, was half-built, and the financial future was most uncertain. Parsons was an ideal candidate to turn things around, because of his knowledge of government research priority interests in the broad field of national security economics and government contracting. By 1965, RTI was solvent and well on its way to becoming the multi-million dollar research and development institution that it is today.

SECOND LIEUTENANT PARSONS

To better understand Parsons’ success at RTI, it is helpful to go all the way back to World War II. In 1945, Parsons was a 25 year-old second lieutenant rifle platoon leader as part of the 69th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army. Life expectancy was about six weeks for rifle company lieutenants, and a disproportionate fraction of the casualties of World War II came from the infantry. Parsons never expected to come home alive from Europe. In fact, unlike many soldiers who married their sweethearts right before being deployed, Parsons never got engaged because he wanted to be sure his insurance and pension benefits went to his mother, who was blind. During his time at war, Parsons first combat against the Germans was in pushing the Germans back from their advances in the Battle of the Bulge. The 69th Division was the lead Division in capturing Leipzig, Germany and was in an ideal position to be committed to the Battle of Berlin, about 45 miles distant. Luckily for Parsons and several tens of thousands of Americans, General Dwight D. Eisenhower opposed Winston Churchill’s priority of American participation in the taking of Berlin. Had the 69th Division entered Berlin, Parsons would have been directly involved in the high casualty requirements of street fighting.

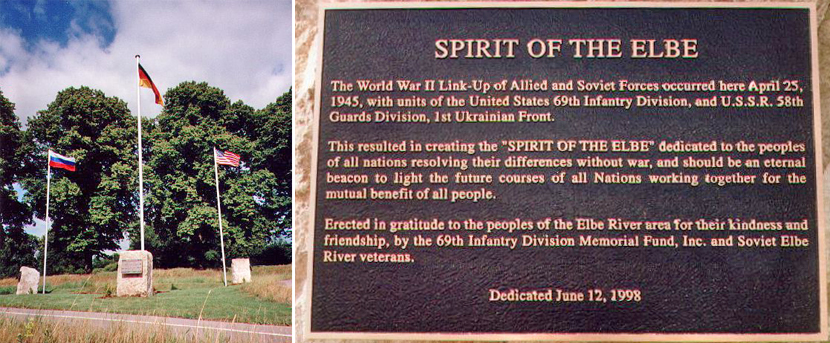

The main objective of the 69th Infantry Division was modified and eventually resulted in linking up with the Soviet Army at the Elbe River in Germany, on April 25, 1945. About two weeks later, the war between Germany and Europe was over, and Parsons’ 69th Division was merged with the 29th Infantry Division, the Omaha Beach Division that first landed at Normandy, France on D-Day and suffered tremendous casualties. The 29th Division was to be committed for the attack on Japan, anticipated to begin in the fall of 1945. On August 6, 1945, the first atomic weapon was dropped on Japan, and the invasion of Japan became unnecessary. Had Parsons been sent to Japan for that invasion, he would not be optimistic about his chances of survival.

In March of 1946, while returning to Germany from an assignment on the Spanish-French border, Parsons happened to meet a psychiatrist who was assigned to the Nuremberg Trials. He arranged for Parsons to be given a press pass that allowed direct access to the courtroom. At the time, Reichs Marshal Hermann Goering was on the stand being prosecuted. Certainly there are few people around these days who can say they were present at the Nuremberg War Trials. Parsons feels extremely fortunate to have been given that opportunity. More fortunate, though, was a seemingly insignificant event in May of 1945, during which Parsons was involved in overseeing the Soviets dismantling a factory in Germany, for shipment to the Soviet Union. That experience, and graduate education, combined some five years later to transfer Parsons’ branch of service in the infantry to the Air Force for service in the Korean War.

PROFESSOR DR. PARSONS

Once Parsons returned home from his military duties in Europe, he decided to complete his Bachelor’s Degree that had been interrupted by the War. He took night classes at the University of Akron while he worked at a tire and rubber factory. Parsons loved the academic life, so he decided to take advantage of the GI Bill and continue his studies in graduate school. He applied to the Master’s Degree program in Economics at Cornell University, but received a rejection letter from them. A few months later, Cornell contacted Parsons to ask why he had decided not to attend their school. He explained that they had rejected him. As it turned out, he had been accepted but had been sent a rejection letter by mistake. Feeling relieved and excited to be able to continue his studies, Parsons headed straight to Ithaca, New York. Once there, he decided to continue on for a Ph.D. in Economics, and finished his dissertation in 1949. He was married in 1947 to Frances Walker, whom he met while she was working at the Library of Congress. In 1950 his first child was born, and life was going well. “When I got my doctorate at Cornell,” Parsons reflects, “I was immediately hired as an Assistant Professor and put on a tenure track, and was looking forward to a life in academia. I bought a farm in Ithica, NY and would be a farmer on the side, and then become a teacher, and frankly, hoped to become a writer of a couple of textbooks.”

Unfortunately, Parsons’ life plan of being a professor and a farmer was not meant to be. “All of that went down the drain when the Korean War broke out and I was really just getting settled in my new home and had a little baby. My daughter was born on May 29, 1950, and the North Korean attack was on the 25th of June. Around July 1st, I got a notice that I would be called to active duty no more than thirty days from then. I was still a Reserve Officer. I knew very well that there was a high probability of my being called back.”

Nevertheless, Parsons at 25 years was in a very different situation from when he first entered WWII. He had a wife and a child and he knew that if he returned to the infantry for the Korean War, he would probably not be as lucky as in World War II. “People are generally unaware of the dangers and the riskiness of being in the infantry, as related to other branches of service or other components in the Army,” Parsons explains. “I’ve heard the statement that in WWII, of the Americans who were in Europe, only 10% ever heard small arms fire. It takes a tremendous amount of support to maintain the fighting front, and I think people are unaware of that. What that really means is that on the front is where most of the casualties were. On the front, the chances of my not being a casualty in Korea were very, very low. When you go back and look at the casualties of the Korean War, that’s where many came from — the trained reservists of the infantry. The possibility of being called back to war initially didn’t bother me a great deal. I knew enough about what I was getting involved in when I stayed in the Reserves, and frankly, I did so in large measure because I needed the money. The money consisted of pay for two weeks in the summer time and one or two days per month for attending various meetings. But I was extremely apprehensive about what was going to be happening to me in Korea. I was a lot different than 4-5 years earlier. I was now a husband and father.”

However, Parsons wished to be involved in Korea, and his outlook took an unexpected turn. “I am an extremely lucky guy. A chance acquaintance at Cornell, who was also a Reservist, said, ‘Bud, because of your previous assignment overseeing the dismantling of that factory in Germany by the Soviets, and your Ph.D., I know very well the Army is looking for guys like you with that kind of background.’ He recommended I go to Washington, D.C. and do some inquiring, and that’s pretty much what happened. Because I had earned a Doctorate in Economics, and also knew quite a bit about industrial production, this made me, frankly, very desirable to the Air Force. The Air Force was still a part of the Army then, so I had no trouble of any kind transferring over. They told me, ‘Don’t worry about being called to Active Duty. We’ll change your branch of service.’ That was a big load off of my mind and also my wife’s mind.”

AT THE PENTAGON

Parsons and his family moved to a rental apartment in Arlington, Virginia, not far from the Pentagon. He was sad to leave the farm and his dreams of being an academic behind, but felt extremely grateful to have avoided infantry combat duty in Korea. “Initially, I worked for the Pentagon in the Air Force. Immediately, I was transferred because of my economic and industrial analysis background, and was put into the intelligence part of the Air Force, helping with the targeting of Air Force weapons and I was then granted full security clearance. At the time, we only had 6-10 atomic weapons and the Soviet Union had detonated their first weapon in September of 1949. The Soviet Union was aggressively expanding the spread of Communism, so I became part of a relatively small group of people who were doing the planning for the targeting of the weapons that we had. The key element of that targeting was the exploitation of intelligence in the Soviet Block and in West Europe that was either of immediate significance or might become significant, so I got involved in intelligence activities right away. I went to Japan and Korea to help do some of the targeting there. One of the most interesting assignments that I had was in early 1953, right after Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected President. During the 1952 election, Eisenhower said in one of his speeches, that he would go to Korea and end the war in Korea. And when he was elected, there were three of us from Air Targets who were sent to Korea to do the targeting for the break out of the Korean Peninsula. By 1953, we had a lot more atomic weapons. The idea was to review the targeting system. I don’t think there was any doubt about United States capabilities at the time. The North Korean Army in effect had ceased to exist by 1953. Although the Chinese threat could have been neutralized, the resulting victory conceptually would have resulted with American and United Nations forces up in Manchuria, the farthest place on the Earth away from our real strength which was located in the U.S. Worse, the United States would be adjacent to the Soviet Union to the North of us. Anyway, we never utilized the atomic weapons, but I think that is a good example of the limited applicability of nuclear weapons.”

During his time with the Air Force, Parsons was also involved in the acquisition of the very first UNIVAC 1 computer that was delivered to the Pentagon in June of 1952. This computer would be used by the Air Force office to which Parsons had been assigned. That office became involved in some of the first “War Games” applications to help understand possible targeting outcomes with computer simulations. “Targeting was extremely interesting because of the relevance of the relationship to the different flows of intelligence. I became involved at a time when “War Gaming” was in its infancy — which I found extremely important and fascinating. This was at a time when computers were first being regarded as an analytical device. About 1952, because of the broad mission of the Air Force, we had a lot of concern about targets. And The Bombing Encyclopedia was developed 60 years ago that highlighted something in the order of 25 million places in the world that the Air Force had an interest in. So there was an immediate interest in modifications in the computer applications that had been developed at Harvard and MIT, to help in the development of artillery firing tables. Computers were being marketed by the company Sperry Rand and we were possible customers for buying the UNIVAC 1. They wanted about $3.5 million for it. The Bureau of the Census was having troubles processing the 1950 Census, so the air force tried to see if they would pay for half of it, and we could share it, but they wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole. The only thing that they would agree on, which turned out to be key, was that they would look at it and try to utilize the downtime for census processing. As you can imagine, as soon as one War Game was held on the computer, with different results, there were 50 different questions that occurred about, ‘What else might be done?’ So there was never any worry about downtime or utility, as soon as the first set of analyses came bouncing out. It really was amazing.”

As the Korean War ended, Parsons stayed with the Air Force in Washington, D.C. and transferred to a job in the Federal Civil Defense Administration, and that organization was reorganized into the Office of Defense Mobilization. “That was extremely interesting because the way of protecting our country was of course to utilize our existing resources so that each of the agencies of government had a special emergency assignment for them to carry out under the event of different levels of emergency. Nowadays, it is no longer in the Executive Office of the President, but is in the Homeland Security Agency.” As interesting as his assignments were in the Air Force, Parsons is a true academic and wanted to return to academia. He also now had four children, and was concerned about raising them in Washington, D.C. “The beltway was not yet built, but one could see it would have a tremendous influence on the continued population expansion. I was living in Falls Church right over the line outside of D.C. at the time.” Therefore, when Bill Howard of RTI approached Parsons in the summer of 1960 about moving to Chapel Hill, N.C. to develop the Research Triangle Institute, as part of the new Research Triangle Park, he was immediately interested.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RTI & RTP*

A BRIEF HISTORY OF RTI & RTP*

While Parsons was working at the Pentagon, big developmental changes were occurring in the heart of North Carolina. Looking back, both RTI’s and RTP’s current success was never guaranteed, nor even fathomable, when the concept for a research triangle park was first introduced by MIT graduate and Greensboro, NC construction company owner Romeo Guest in 1954. His vision was to combine the resources and intellectual talent of the three principal universities in the heart of North Carolina, namely UNC-Chapel Hill, NC State College, and Duke University, in a collaborative effort to support a research park. The principal goal was to help bring industry to rural North Carolina. At the time, North Carolina’s economy was based primarily on tobacco, textiles and furniture production, though these three industries were waning during the post World War II era. North Carolina had more farms than any other state except Texas, and ranked second, after Mississippi, in poorest per capita in the United States. The other crisis North Carolina was facing was the intellectual flight of its most educated citizens. These three top universities produced a population of brilliant academic scholars who simply could not find work anywhere in the state, forcing them to relocate away from home to urban areas for employment.

The governor of North Carolina during the mid-1950’s was Luther Hodges, and he was determined to figure out a way to create a more stable and thriving economy for the state. In 1954, Guest presented his idea for RTP to Hodges and immediately received Hodges’ enthusiastic approval of the project, along with support from UNC-Chapel Hill’s President Gordon Gray and Duke University’s President Arthur Hollis Edens. Hodges could not allocate state funds for the project, but he invested so much of his personal time and energy into it, it became known as the Governor’s Research Triangle. He believed, as did Guest, that this was the best way to create jobs here in North Carolina. Hodges then brought in Robert Hanes, who was the president of Wachovia Bank, to head the new Research Triangle Development Council that was established to endorse Romeo Guest’s idea, along with powerful North Carolina businessmen, politicians and academic elite, including Brandon P. Hodges, UNC-Chapel Hill’s new president William Friday, Robert Armstrong, E. Y. Floyd, Grady Rankin, C. W. Reynolds and William Ruffin. In 1956, George Simpson, a UNC-CH Sociology professor was hired as Executive Secretary, at the recommendation of President William Friday. Simpson successfully obtained the support from the faculty of the three universities, which was integral to this program’s success.

The next step was to acquire land for the park, and Hodges and Simpson together convinced Karl Robbins, a NC textiles businessman, to invest $1 million to purchase a tract of land near RDU airport. Then they authorized Romeo Guest to buy an option property in the name of The Pinelands Company Incorporated. They kept the intent for the use of the land secret from the seller, in order to not drive up prices for this tract of infertile farmland. On Sept. 10, 1957, Hodges went public and announced the plan for Research Triangle Park to the Press. On Feb 10, 1958, 4,000 acres had been purchased or optioned at an average price of $175/acre.

Nevertheless, convincing northern companies to relocate to the southern state of North Carolina was a tough sell. There were two especially unfavorable conditions present during that time: segregation was still in place, and the public school system was substandard in comparison with northern schools. By the summer of 1958, the project was in serious trouble. There were no new investors and options payments were coming due, so Pinewoods was about to lose most of its land. Hodges decided to dedicate one person to sell stock in Pinelands. Robert Hanes suggested Archie Davis, chairman of Wachovia Bank. Davis had an interest in wanting to improve North Carolina and believed that building the Park was the way to do it. He decided it needed to become a nonprofit and join the public arena, so that local corporations would be more willing to donate funds for the betterment of the state North Carolina. His goal was to raise $1.25 million from contributors, and because he was well connected, persuasive and widely admired, he ended up exceeding his goal and raised almost $1.5 million in cash. Many of the contributors were friends of Hanes, who had just been diagnosed with terminal cancer. The money would be used three ways: the land would be passed to the newly formed nonprofit Research Triangle Foundation, the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) would be established, and a building would be built on the land to house RTI. The Hanes family personally donated $300,000 and requested that the first building of RTI be named after Robert Hanes. Hanes died two months later, but the Hanes building still stands in the heart of RTP in honor of his memory and contribution.

With funding in place, RTI began hiring its key employees. In December of 1958, Dr. Gertrude Cox, founder and director of the joint UNC/NC State Institute of Statistics, left NC State College to direct the statistics research division of RTI. More importantly, she brought with her a long list of government and corporate clients to the new Research Triangle Institute. George Watts Hill, a Durham banker, was named Chairman of RTI and held that position for 34 years. In January of 1959, Hill hired George Herbert, former Associate Director of the Stanford Research Institute to be RTI’s first president, and also Parsons’ immediate superior. William Little was appointed by UNC-Chapel Hill’s President William Friday to be on the Institute’s Board of Governors, Governing Committee. Another executive who was hired by George Herbert and Gertrude Cox was Hugh Mizer, who in turn hired Bill Howard.

In May of 1959, Research Triangle Park got its first official tenant. Chemstrand, a manufacturer of acrylic and nylon, was going to relocate its lab from Decator, Alabama to Princeton, New Jersey. William Little convinced Chemstrand to build a large research facility in RTP instead, thanks in part to N.C. State College’s nationally acclaimed textile program. The initial success of both RTI and Chemstrand gave much-needed credibility to RTP, as they were the two anchor companies there. Things were looking up, but then the momentum stalled and development at Research Triangle Park came to a complete halt.

PARSONS ARRIVES IN CHAPEL HILL, NC

In the summer of 1960, as Parsons was looking around for academic-related employment opportunities, he was contacted by an RTI executive about the possibility of coming to work at the new Research Triangle Institute in North Carolina. “The guy that brought me to Chapel Hill was a guy named Bill Howard. Bill knew me because he previously worked for the Library of Congress and one of my jobs for the Air Force was to supervise two projects at the Library of Congress. I was the contract guy for the Air Force, so he put my name in the hat here for RTI. We received an invitation for me and my wife Frances to come down and look around.” Parsons had never visited Chapel Hill before, but he had heard all about what a wonderful place it was from a colleague at the Pentagon. “I shared the same office with a guy named Jimmy Walker, who had gotten his PhD from Carolina. Any number of times we would go out to lunch, he would always say his idea of happiness was to live in Chapel Hill. I must have heard that a dozen times. Anyway, I came down here and I saw it as a good opportunity to get back to academic work.” Parsons also felt that this quiet, small town would be a much better environment in which to raise his four children.

There was still not an RTI facility built at RTP when Parsons arrived. “We were working out of temporary offices in Durham, NC in the Home Security Life Insurance building, which was the home office of George Watts Hill, a leading Democrat and one of the dedicated promoters of the Research Triangle Park. There were only two buildings on the land at RTP at the time. One tiny building about the size of a house, was run by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that had about six people working there. The other was the new Chemstrand building. Those were the only two buildings out there. Research Triangle Park was still just a dream.”

Parsons did not know at the time that RTI was in serious financial trouble. “I was sufficiently interested in the position, but I did not look carefully into the finances of the Institute. I had the impression that they had a fund of at least $500,000 a year because they referred to a similar organization in Princeton, New Jersey. Matter of fact, it was the organization that hired Oppenheimer. They were using the Princeton and Stanford Research Institutes as models, and Stanford was very well funded and they meant to emulate SRI.” In reality, RTI only had $500,000 total to start out with, and before it was even built, RTI had almost run out of funds. “I was only here about 4 months when in one of the management meetings, Herbert laid the dollars out in front of us. That was a great awakening, because I realized then that there was not $500,000 a year. The subject of the meeting was ‘Who Can We Lay Off?’ I had four kids and my house was well under way of construction.”

Because of Parsons’ background in economics and his experience working in the Federal Government, he quickly realized the main cause of their financial woes and began working diligently to turn things around at RTI. “I knew a lot about what had to be done, and was able to do it, by virtue of my previous position in Washington. I had come to know quite important people in every one of the departments and agencies, and I knew my way around Washington. There had been a guy, hired ahead of me, by the name of Hugh Mizer. Wonderful guy. Very smart guy. Very capable. But in effect, knew very little about contract research. Mizer and this relatively small group of people, 20-25 people that had been hired by George Herbert and Gertrude Cox, had to have a cash flow. $500,000, even 50 years ago, would not last very long. With all respect to Mizer, a very smart guy but without any real knowledge or know-how on how the government worked, was not being successful in the slightest in tapping government funds. RTI was trying to figure out, through grants, how to get more financial means. Mizer had been given something that I’ll call Operations Research and had received a certain cache in academic and other circles, but it takes a special know-how on how the government works. And also in the matter of security clearances, I had them all. Not only that, but several other research organizations across the U.S. had just gone out of business. Northstar, centered around the University of Wisconsin with Hubert Humphrey, and Spindle Top, centered around The University of Kentucky and the Kentucky money – they were all trying to do the same thing that SRI did. But you had to know your way around the government and understand the way that government works. I knew for certain that there would be no RTI without government funding. I suspect well-over 90% of RTI’s current work comes from the Federal Government.” (According to RTI International’s Annual Report from 2011, 85% of their total revenues are indeed government funded.)

Parsons explains the process this way. “We operated almost exclusively on contracts. Universities could get a grant because the University could sign off on the fact they want to do something, and they’ll get what they call a grant because it is considered part of Grant and Aid. Then you look them in the eye and they are not going to do it unless they get the grant. But at least they can say, ‘This is what we would like to do and we have faculty on board.’ So there is a very major difference. At an organization like RTI, you have to get a contract, which means you have to perform. You have to come up with the idea, you have to sell it to someone who has got the money, and then you have to perform. It’s a contract.”

Over the next ten years, with Parsons at the helm in charge of obtaining and managing contracts, RTI’s government contracts grew continuously, and therefore so did its funds. Many of them were highly secure government research projects that only someone with Parsons’ security clearance and previous military experience could handle. “My first contract for RTI was actually for SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers of Europe.) It was the analytical arm of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. I did research for them, including quite a bit of travel back and forth to Europe. It was a classified contract. It worked out very well, and it was also the basis then to frankly get a lot of projects in the Pentagon for things that I had been doing before that were quite technical and classified.”

The other advantage for RTI having Parsons in this position was his previous academic experience at Cornell University. He was a Ph.D. from an Ivy League University, which was an extremely prestigious degree to have during that time. “Ph.D.’s were a lot different than they are today. For example, I could be off a little on these numbers, but the year I got my PhD from Cornell, I was in a class of some 2,000 in the United States. The last figure I remember on the annual production of PhD’s is that now we are turning out 36-38,000 a year. It’s a totally different ball game today.” His academic qualifications and connections to academic elite were extensive, which proved paramount in obtaining these contracts. “I had innumerable conversations with eminent professors and faculty members who had expertise in some particular area, that was very helpful and may have been crucial to actually getting these contracts. They are supposed to contribute a chapter or something on a particular aspect, which is the key to getting a contract in the first place. And with that as a background, you have an eyeball-to-eyeball discussion with the faculty member. So to get the contract, like a University, you had to have the muscle behind you, the research scientist or the expert in the field. You had to have the people to perform. You don’t write the contract until you have the people lined up. Working at RTI was a very good fit for the connections I had.”

THE DEVELOPMENT OF RTP

Thanks in large part to Bud Parsons’ efforts, RTI was finally becoming financially stable. But there was still the problem of wooing potential corporations to RTP itself. Parsons remembers, “There continued to be very serious problems. By 1963, it was starting to be very obvious that there was not much expansion in RTP — pretty close to zero. No one else was interested in moving out there. There was a major company that wanted to locate in the Park, and all of the details had been worked out except one. That detail had to do with the restriction against the production on whatever commodity it was, and if the research turned out to be OK, they wanted to go into production. The arrangement for RTI, as was the Stanford Research Institute, was that none of their land would ever be used for production. But the company was confident that the restriction would be removed or modified. But it wasn’t. So the company decided not to relocate here. Because of that, there was a significant change made in the zoning of the Research Triangle Park. That change had to do with the proportion of managerial and direct research employees. And once that restriction was removed, RTP became an Industrial Park, not a Research Park. But the people who had that restriction removed, simply said, ‘Hey, there is nothing to stop us from continuing to call it a Research Triangle Park.’ In reality, it’s an Industrial Park, but we still call it a Research Park. That was not the original intent of the Park. They wanted it to be strictly a research hub, not a production hub. No air pollution, to chemical pollution, none of that. Everything nice and clean and pure. From that time on, however, things changed.”

Nevertheless, with the production restriction removed, business finally started becoming interested in the area. What started off the revival of development in RTP was due to efforts made by Luther Hodges’ successor, Governor Terry Sanford. On his last day in office in January of 1965, Sanford announced that RTP had been selected for a massive US Environmental Health Sciences Center. Now known as NIEHS, it employs almost 1,000 people and conducts biomedical research on the effects of the environment on human health. Later in 1965, another huge boon came when IBM officials decided to locate a $15 million research facility on almost 400 acres in the park. Having the land rezoned to accommodate production was one of the crucial aspects about the decision of IBM to locate a facility there. They could now conduct research and produce products all at the same facility. With IBM’s huge land purchase, the Research Triangle Foundation was able to completely pay off its mortgage for the land. Now IBM is RTP’s largest organization with over 14,000 employees, and has developed strong relationships with all three Universities. The presence of IBM confirmed RTP’s success, and an abundance of companies soon followed, including Burroughs-Wellcome, The EPA, Glaxo, Nortel and CISCO Systems.

92 YEARS YOUNG

In 1971, after working at RTI for ten years, Dr. Parsons left his job there to become Vice-President of System Sciences, Inc. “The major reason I left RTI was that I was involved with so many different projects with so much travel involved. I had four kids, and I remember in that two-year interval, I had spent half my nights away from Chapel Hill. I had projects all over the world, and a major project in Tehran, Iran. I was offered a large sum of money to set up a branch for System Sciences, Inc. in RTP, and my new position allowed me to stay in Chapel Hill and spend more time with my family.”

Parsons retired from System Sciences in 1981, and since his kids were all grown, he spent a few years traveling the world with his wife, Frances. In the mid-80’s, Frances became ill and Parsons took care of her at their home until her death in 2005.

He also spent 1985-1995 establishing a Torgau Memorial and Peace Park along the Elbe River in Germany to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the 69th Infantry Divisions “East Meets West” link-up with the Soviets during WWII, which is still celebrated yearly on Elbe Day in Torgau, Germany. “For those ten years, I went back to either Germany or the Soviet Union about once a year on all kinds of arrangements, leading up to the dedication of this park on the 50th Anniversary of the meeting. The Soviets still have April 25th as an important date of their Military history, almost like we have June 6th, as it signified the end of the war for them.”

Always a professor at heart, Parsons became actively involved with a local Chapel Hill group of retirees called Shared Learning. It is an informal school where retirees teach retirees. “The first class I taught was on the Vietnam War. And then I started a class called Our times and Our Presidents and I started with Herbert Hoover and it took me five years of that class until I brought it up to current times. Then I started all over again. Because it was our times, people had their own recollections. And then I got involved in the Civil War and that took me a couple of years. It took me about 2 months to get through the Battle of Gettysburg alone! We went into it in considerable detail.”

Even at 92 years old, Parsons still attends classes at Shared Learning. He no longer teaches, as his voice is too weak to deliver a lengthy lecture. However, he is occasionally asked to give talks about the vast amount of knowledge and experience he has gathered in his 92 years. Just last month, he was invited to speak to the Lake Forest Garden Club about how Eastwood Lake has changed over the last fifty years of his living on it. “When we moved here, there were about 6-10 seagulls living on the lake. For a year or two, we would have snowy egret on the lake. We still have 1-2 blue herons and a lot of ducks that go from our lake to Lake Ellen and Colony Lake. There also used to be a fairly active dairy farm, up Shady Lawn Road at the top of the hill beyond North Lakeshore Drive, and I can still remember the cows mooing away. And we used to have, I am told, a couple of foxes living around here, as well.”

After living in Chapel Hill for over fifty years, Parsons has seen a lot of changes to the area. “When we first moved here, there was only one traffic light in Chapel Hill at Franklin Street and Columbia Street. It was not up in the air, it was in the top of a cement pillar about 5’ high at eye level if you were sitting in the car. At and Thanksgiving, Christmas and over the summer, the town would just shut down — there were no students around. We used to have the Chapel Hill Weekly newspaper, as we called it, and on the day classes opened up in the fall, they would always have a big front-page headline that read, ‘Welcome Back Money!’ We went to Franklin Street a lot, and right across the street from where the Siena Hotel is now, there was a drive-in. The movie theatre was where Ram’s Gate is now. There was a hill, and against the side of the hill there was a screen, and I would pile all the kids in our station wagon and go see the show. And where the Holiday Inn is, there was a driving range. Chapel Hill was a smaller and quieter town back then, but I still enjoy living here very much.”

If you happen to drive down North Lakeshore Drive in the early evening, you can usually catch Parsons taking his daily, two-mile walk up and down the steep hills around his neighborhood. I highly recommend you pull over and stop to speak with him. His memory is as sharp as a tack, his gentle spirit is endearing, and his humble brilliance is inspiring.

THE LEGACY OF DR. EDGAR PARSONS

Dr. Parsons’ many contributions during his ten years at RTI came at a crucial time when the success of Research Triangle Park was still yet to be determined, and was extremely dependent on the success of RTI. Thanks in large part to Parsons’ timely arrival, expertise, governmental and academic connections, and insight into how to bring RTI back from serious financial trouble, the Research Triangle Park has forever changed the landscape and economy of North Carolina. Not only can graduates from our outstanding universities now find work here and stay in North Carolina, but also working in RTP has become so competitive and internationally renowned, it brings thousands of skilled workers from all over the globe to our fair state. Thank you, Dr. Parsons!

*Source: The Research Triangle Park: An Investment in the Future, written, directed and produced by John Wilson and narrated by Carl Kasell.

Category: People, Popular Articles

I had the great pleasure of being able to spend a week with Bud in 2001

As this article says, he was a wonderful and very impressive person, and had an amazing career.

He is missed.

Vin McMaster

Dallas, Texas

Thank you for your kind words, Vin.